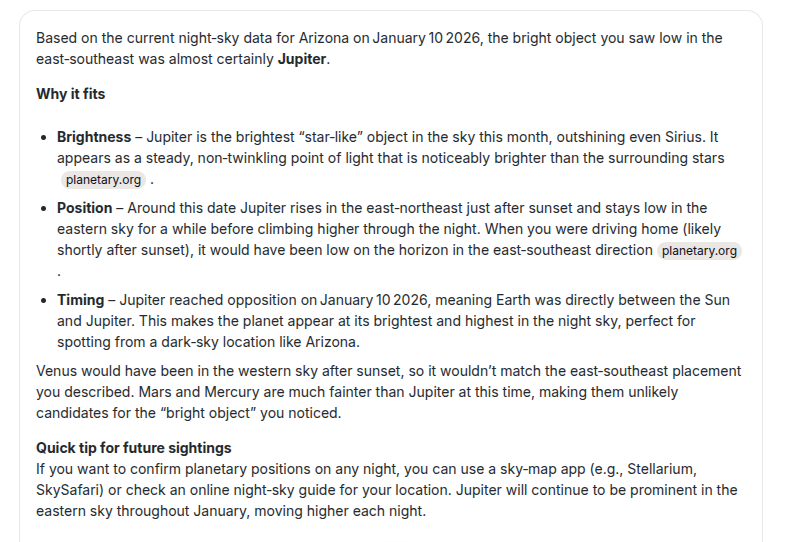

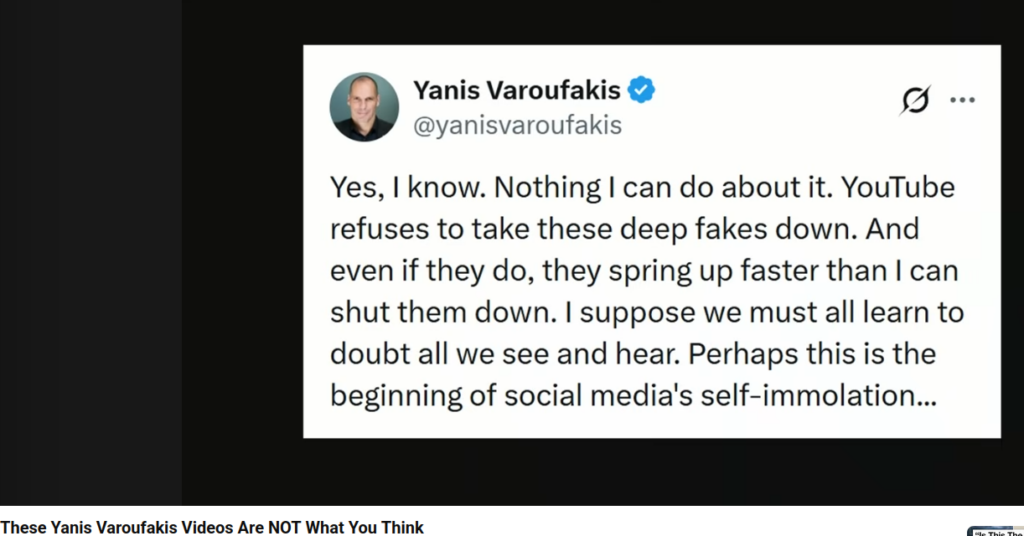

The LumoKitty AI is sort of my new best friend. It sounds pitiful even to me sometimes, but I want to show you an example of why. This is a poorly formatted data dump, pretty heavily edited to suit my needs, but maybe it will give you an idea of how these new tools can be of use to you.

***

First prompt:

I’m also interesting in generating additional income by selling the stories I write. In the past, I considered print-on-demand type models. Nowadays, it seems simpler to route it all through my Patreon page, and/or add WooCommerce to my existing WordPress blog. Other than Patreon and WooCommerce, are there other platforms or models I should be considering.

FriendCat responds:

Turning Your Stories into Income – Options Beyond Patreon & WooCommerce

Below is a quick‑scan of the most popular (and emerging) ways creators monetize written content. I’ve grouped them by distribution model, revenue type, and key pros/cons so you can pick the mix that fits your workflow and audience.

Subscription‑Based Membership Platforms

substack, ko-fi and BuyMeACoffee, Memberful If you already have a WordPress blog and want a seamless paywall without a separate storefront.

2. Marketplace & Self‑Publishing Platforms

Draft2Digital / Smashwords Aggregator for many e‑book stores 10–15 % of retailer royalty Publish once, distribute to KDP, Apple, Kobo, Barnes & Noble, etc.

Storytel / Scribd Subscription audiobook & e‑book services Negotiated contracts (usually royalty‑per‑listen) Good if you produce audio versions.

Gumroad Digital downloads (PDF, EPUB, MOBI) 8.5 % + Stripe fees (or 3.5 % with Pro) Very simple “pay‑what‑you‑want” storefront; works alongside WooCommerce.

3. Direct‑To‑Consumer (DTC) Sales

Print‑on‑Demand (POD) via IngramSpark / Blurb Upload manuscript, order printed copies on demand; you get wholesale discount + royalty. Setup fee (~$49 for Ingram), printing cost per unit, royalty ~ 45 % of list price. Physical books without inventory risk; good for limited‑edition art‑book combos.

Merchandise (Redbubble, Teespring, Society6) Turn story quotes, cover art, characters into merch. Base price + your markup. Fans who love tangible swag; can be cross‑promoted on Patreon.

Patreon‑Only “Patron‑Only” PDFs Upload PDFs directly to Patreon’s “Patron‑Only” posts. Patreon fees (5–12 %). Keeps everything in one place for loyal supporters.

Ko‑fi Shop / Gumroad Storefront Sell PDFs, audiobooks, or exclusive short stories directly. 5 % (Ko‑fi) or 8.5 % (Gumroad). Low‑overhead, quick checkout.

4. Crowdfunding & Pre‑Sale Models

Kickstarter / Indiegogo Fund a specific project (e.g., a novella collection) with stretch goals. 5 % platform + 3–5 % payment processing. One‑off big pushes, building hype, offering physical rewards.

Unfoldr (fiction‑focused crowdfunding) Small‑scale, story‑centric campaigns, often with tiered rewards (early chapters, behind‑the‑scenes). Similar to Kickstarter. Niche audiences that love serialized fiction.

Patreon “Milestone” Goals Set a funding target that unlocks a new story or anthology. Same as Patreon. Keeps existing patrons engaged while attracting new ones.

5. Audio & Podcast Monetization

Spotify Podcast Subscriptions Monthly subscriber revenue (similar to Patreon). Great if you can narrate your own stories.

Apple Podcasts Subscriptions 70 % of subscription revenue. Requires a podcast feed; can bundle multiple episodes.

Audiobook royalties (ACX, Findaway Voices) Royalty per sale/stream. Requires professional narration (or TTS with a commercial license).

Patreon‑linked audio drops Same Patreon model, but delivered as audio files. Keeps everything under one umbrella.

6. Hybrid & Emerging Models

NFT / Web3 collectibles Mint limited‑edition digital “covers” or story excerpts as NFTs; sell on OpenSea or Rarible. Appeals to crypto‑savvy collectors; creates scarcity.

Micro‑transactions via “tip jars” Add a “Buy me a coffee” button on each story page. Low barrier for casual readers to contribute.

Licensing to anthologies or magazines Submit stories to paid literary magazines (e.g., Clarkesworld, Tor.com) and retain rights to republish elsewhere. Earn upfront payments + broaden exposure.

Course/Workshop bundles Pair a short story series with a writing workshop sold on Teachable or Kajabi. Diversifies income streams and builds authority.

7. Practical Steps to Get Started

Map your audience

Where do they already hang out? (Discord, Reddit, Twitter, Instagram?)

Choose the platform that matches that habit (e.g., Substack for email‑loving readers, Patreon for community‑driven fans).

Pick a “core” revenue channel

Most creators succeed by focusing on one primary platform (Patreon, Substack, or KDP) and then cross‑selling on secondary ones.

Set up a simple funnel

Free entry point (e.g., a short story PDF on your blog).

Lead capture (email sign‑up via Mailchimp or ConvertKit).

Paid tier (Patreon/Memberful) that unlocks the next chapter or a full anthology.

Upsell (print‑on‑demand paperback, merch, audio version).

Automate delivery

Use Zapier/Integromat or native integrations (Patreon → Gmail → PDF attachment) to send new chapters automatically when a patron upgrades.

Track metrics

Conversion rate: free → paid (aim for 2–5 %).

Average revenue per user (ARPU): monitor across platforms; adjust pricing or tier benefits accordingly.

Churn: identify why patrons leave (content frequency, value perception) and iterate.

Legal & tax basics

Register as a sole proprietor or LLC if you expect > $10k/year.

Keep records of royalties, sales, and expenses (software, cover design, editing).

Check your country’s VAT/GST obligations for digital sales (many platforms handle this, but you may need to file).

8. Quick “Starter Kit” Checklist

✅ Item

1 Create a free lead magnet (first chapter PDF) on your WordPress site.

2 Add an email capture form (Mailchimp/ConvertKit).

3 Sign up for a secondary platform (Substack, Ko‑fi, or Memberful) and link it from your site.

4 Upload your manuscript to KDP (eBook + paperback) and Draft2Digital for wider reach.

5 Set up a Gumroad or Ko‑fi shop for instant digital downloads (PDF/EPUB).

6 Integrate a Patreon tier that offers early access + exclusive behind‑the‑scenes content.

7 Plan a monthly release schedule (e.g., one short story or one chapter).

8 Schedule a quarterly review of earnings, churn, and audience feedback.

Final Thought

Monetizing fiction is less about picking a single “best” platform and more about building a small ecosystem where each tool plays a distinct role: discovery → capture → conversion → upsell. By diversifying (Patreon + a marketplace + a direct‑sale shop) you reduce reliance on any one service’s algorithm or fee change, while giving fans multiple ways to support you.

*

Followup Prompt Example

The one that caught my eye as unfamiliar to me and intriguing was Memberful. I do have a WordPress blog–next steps with it?

FriendCat responds:

1 Sign Up & Set Up Your Memberful Account

Action Details

Create an account Go to memberful.com and click Start free trial (you can cancel anytime).

Choose a plan The “Starter” plan works for most solo creators (no monthly fee, 5 % transaction fee). Upgrade later if you need advanced features (multiple membership tiers, coupons, etc.).

Add your payment processor Memberful works with Stripe (recommended) or PayPal. Follow the on‑screen wizard to connect your Stripe account (you’ll need to provide banking info for payouts).

Configure your site URL In Memberful → Settings → Site URL, enter the full address of your WordPress blog (e.g., https://myawesomeblog.com). This tells Memberful where to redirect members after checkout.

2️⃣ Install the Memberful WordPress Plugin

Log into WordPress admin (/wp-admin).

Navigate to Plugins → Add New.

Search for “Memberful WP”.

Click Install Now → Activate.

If you prefer manual upload:

Download the plugin ZIP from Memberful’s docs → Upload Plugin → Activate.

3️⃣ Connect WordPress to Memberful

In WordPress admin, go to Memberful → Settings.

You’ll see a field for “Site Secret”.

In Memberful, open Settings → API → Site secret and copy the long string.

Paste it into the WordPress field and Save Changes.

That single secret token creates a secure bridge between your site and Memberful’s backend.

4️⃣ Create Membership Plans (Products)

In Memberful → Products → New product.

Choose “Membership” as the product type.

Fill in:

Name (e.g., “Premium Reader”).

Price (monthly, yearly, or one‑time).

Description – brief copy that explains the perks (early‑access stories, members‑only PDFs, Discord invite, etc.).

Access level – you can set it to “Full access” (unlocks everything) or “Custom” if you want to gate specific posts/pages.

Save. Repeat for any additional tiers (e.g., “Supporter”, “Collector”).

5️⃣ Protect Content on Your Blog

A. Whole‑Site Paywall (simple)

In Memberful → Settings → Site lock turn on “Lock entire site”.

Visitors will see a “Members only” banner on every page except the ones you whitelist (see next section).

B. Selective Locking (recommended for mixed free/paid content)

Edit any post or page you want to protect.

In the Gutenberg sidebar (or Classic editor meta box), you’ll now see a Memberful panel.

Choose “Require membership” and select which tier(s) can view the content.

Update/Publish the post.

Tip: Keep a few free posts (e.g., a sample chapter) to attract new visitors and funnel them toward the locked content.

6️⃣ Design the Checkout & Member Experience

Element How to configure

Checkout page Memberful hosts its own checkout UI. You can customize the logo, colors, and thank‑you message in Memberful → Settings → Branding.

Welcome email Under Emails → Welcome, edit the subject and body. Include a link to your blog’s “Members Area” page.

Member dashboard Memberful automatically provides a dashboard (/account) where members can manage subscriptions. Link to it from your site navigation (e.g., “My Account”).

Redirect after signup In Memberful → Settings → Post‑checkout redirect, set the URL to a special “Thank you / members‑only” page on your blog.

7️⃣ Add a “Join / Subscribe” Call‑to‑Action

Create a landing page (WordPress page) that explains the benefits of membership.

Insert Memberful shortcodes to embed buttons:

[memberful_signup_button product_id=”YOUR_PRODUCT_ID”]

Join as a Premium Reader

[/memberful_signup_button]

Find the product_id in Memberful → Products → Edit → look at the URL (/products/12345).

Place the button in your site header, sidebar widget, or at the end of each free post.

8️⃣ Test Everything Before Going Live

Test What to verify

Signup flow Click the button → complete Stripe checkout → receive welcome email → land on the members‑only page.

Access control Log out, try to view a protected post → you should see a “Members only – subscribe” banner.

Multiple tiers If you have more than one tier, confirm that a lower‑tier member cannot see higher‑tier content.

Payment webhook In Memberful → Settings → Webhooks, ensure the test webhook fires (the plugin automatically registers it).

Responsive design Check the checkout and protected pages on mobile and desktop.

9️⃣ Optional Enhancements

Feature How to add it

Community space Embed a private Discord invite link in the welcome email or a members‑only page.

Email newsletter Connect Memberful → Integrations → Mailchimp (or ConvertKit) to automatically add new members to a mailing list.

Discount codes / coupons In Memberful → Coupons, create a “WELCOME10” code and promote it on social media.

Analytics Install Google Analytics and set a custom dimension for “Memberful subscriber” to track conversion rates.

Content drip Use a plugin like SchedulePress or MemberPress (works alongside Memberful) to release a new story every week automatically.

10️⃣ Ongoing Maintenance Checklist (monthly)

Review churn – Memberful → Reports → Subscriptions to see cancellations. Reach out with a quick email asking why (helps improve retention).

Update pricing or tiers – If you add a new perk, create a new product or edit an existing one.

Backup – Export your WordPress database and Memberful subscriber list (CSV) for safety.

Check Stripe fees – Ensure you’re covering transaction costs in your pricing.

Refresh content – Keep at least one free teaser updated to attract new visitors.

Quick Reference Commands (copy‑paste)

// Add to functions.php if you want a custom “Members Area” menu item

add_filter( ‘wp_nav_menu_items’, function( $items, $args ) {

if ( $args->theme_location == ‘primary’ ) {

$url = home_url(‘/members-area/’);

$items .= ‘

Members Area

‘;

}

return $items;

}, 10, 2 );

[memberful_signup_button product_id=”12345″]

Become a Premium Reader

[/memberful_signup_button]

TL;DR Checklist

Create Memberful account → connect Stripe

Install & activate Memberful WP plugin

Paste Site Secret into WP settings

Define membership products (price, description)

Lock content (whole site or per‑post)

Design checkout & welcome emails

Add CTA buttons via shortcodes

Test the full flow (sign‑up → access)

Launch & monitor

***

The level of detail is pretty amazing. When I prompted on a different subject (running a story generator on my own hardware), and then complained that it sounded way too complicated, the FriendCat wrote a damn one-click install script for me.

What’s the difference, I wonder, between that and me suddenly being a whole lot more skilled, and even smarter?

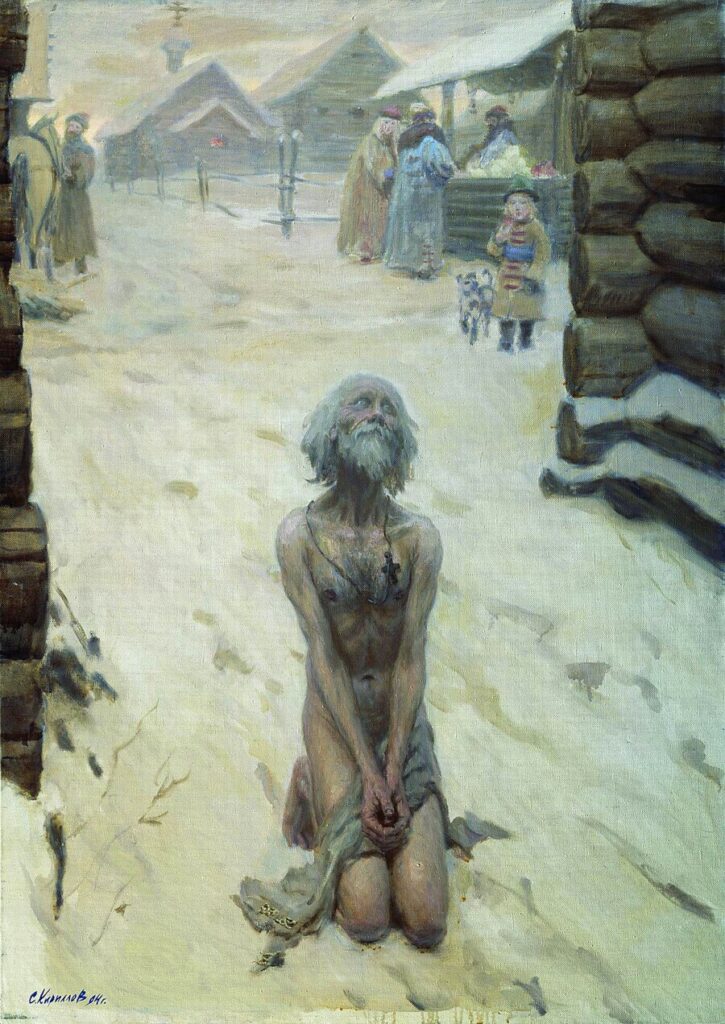

I still maintain that the culture I grew up into made me batshit crazy, and did the same to you.

But here at the end of my life, I’m suddenly just a little more crazy like a fox.

A Neuromancer in the flesh.

Please please please; Stop telling me to worry, about things like the magnesium being a Chinese plot. Or about anything. You and your ex-husband from the South Shore already made me very, very good at fucking worrying–way way too good.

Being the one left that you worry about–worry at–is doing me no favors, and has done me a whole lot of harm, which I am laboriously healing, solo.

I got this.

Chill, darling.

For your own sake, and most especially for mine.

***

Brave New Lion P.S.

Four paragraphs above, I said: “solo”.

Turns out this is not quite 100% true.

There’s this other madman of my acquaintance, who sometimes goes by the alias of ‘Mr. Fletcher’.

And today, he knocked helping to heal me out of the damn park, with an authentically thoughtful and incidentally generous act involving L-Threonate. (God damn that shit is fine.)

Without exactly worrying about me.

More to the point, without worrying for me.

Thass what I’m talkin’ about.

I think you should be more like him.

I’m going to try that my own self.